Articles, Interviews

Exotic Dancing in The Digital Age – Medium

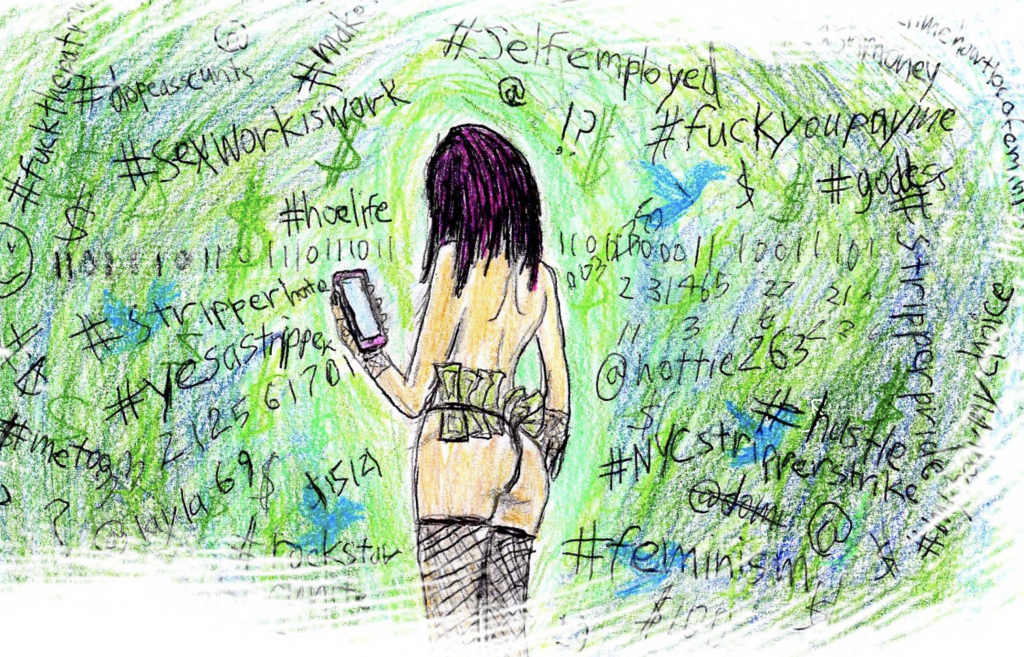

How technology is changing how strippers view themselves, interact with society and do business

“I could be a stripper.”

That was what Juniper thought to herself during an eight-hour drive to visit some out of town friends. She had just broken up with her boyfriend and felt like her life was going nowhere.

“I had been working independently as a housekeeper for 5 years, but I wasn’t making enough to actually change my situation,” she explains. “As I drove I kept thinking of different ways to improve my life and I jokingly thought to myself ‘I could be a stripper.’ But then the more I thought about it the more it seemed I could actually do it.”

She’d already embraced a love of bondage and considered herself a bit of a kinkster. She wasn’t self- conscious about her sexuality and wasn’t bothered about being naked around others, she reasoned that putting on a nude performance for cash wouldn’t be that crazy of a way to start making money.

After dancing for a while, Juniper (her stage name) changed her Instagram handle to @wandering.stripper and hit the road in an RV. “It was very freeing to be able to travel wherever I wanted and pretty much instantly seek employment,” she explained. She documented her trip, telling her followers which clubs she was stopping at along the way, as well as posting her adventures in the outdoors as she made her way across the country.

Juniper is one of many strippers who have become increasingly comfortable sharing their lives on Social media for the world to see. In recent years strippers have taken to Instagram and other social media platforms to advertise performances and build up a fanbase — not unlike musicians, comedians and other performance artists.

They are also using these tools to fight stereotypes about their profession, demand better working conditions and create professional support networks. It’s creating new opportunities and challenges. And at times new risks.

Strippers are rarely employees at clubs and more commonly work as independent entertainers that clubs use as a draw to bring people in. In many venues, they often pay a stage fee to perform and ultimately keep whatever money is left over after they’ve counted up all of their tips.

But even after that it can still be lucrative work. A 2010 Leeds University study found that on the higher end some strippers in the U.K. take home as much as 48,000 pounds ($74,500) annually.

Gia, a Miami-based stripper, runs a new organization called Strippreneur, which she wants to be a platform for strippers to fight for recognition and find professional resources. She got her start dancing in her home state of Tennessee while she was going to school.

“I was working three jobs and that was depressing and time consuming. I had always been in the art field and knew I wanted to pursue fashion,” she says. After receiving a steep pay cut at one of her jobs, she quit and decided to try stripping. “I realized I was spending too much time in their space and I can do it differently.”

Today Gia is a champion multi-tasker. She has her own designer clothing line called Gia Perrotti in addition to being an active dancer and raising a kid. She keeps up to date reading business news and carefully studies the way that other entrepreneurs have branded themselves and handled their money. She’s developed a particular admiration for business mogul Warren Buffett.

“I love that he amassed this massive fortune and still lives in a normal house,” Gia says. “I’ve made stupid amounts of money in a week and will still go to a local thrift store and by a pair of jeans for a dollar. I love how he doesn’t allow the norm to dictate what he does or what he wants to do.”

Gia frequently mentors other dancers, talking to them about their careers and what they want to do with their money.

“I think a lot of dancers don’t recognize that they are independent contractors, and if they do, they don’t often get into everything that means … I want strippreneurs — or any dancers — to maximize the time,” she explains. “Even if its dedicating a two hour block to some entrepreneurial goal, whether it’s introducing yourself to a new book, introducing yourself to a new circle, you know there’s so much information that’s readily available. And when you’re in the night life and in the dancing world you have opportunities that people don’t have, because they’re on someone else’s clock and they have to wait to be paid.”

Social media has transformed how dancers promote themselves and manage their careers. With pages on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter strippers can advertise their dance schedules, telling fans and regulars which venues they will be performing at and when, as well as make themselves available for private bookings — many dancers double as models.

“Freelancers will always have to find out how to be self-supporting and sustainable,” explains Elle Stanger, a stripper and pro-sex worker activist based in Portland, Oregon. “But when those freelancers are women working in a highly stigmatized industry, we will encounter more obstacles than other freelance hustlers.”

But social media can be a double edged sword in a business that largely depends on in-person, cash transactions.

“You have girls being able to give shows on Instagram, you have girls using it to do advertising, a lot of the things that were in the club are now on social media,” Gia explains. “In one aspect I think that’s beneficial and in another aspect I think it’s detrimental because at the end of the day if a guy can turn on his Instagram and Snapchat and see you all day, what’s the incentive for that man coming to see you in person?”

But where a particular stripper lives and works makes a big difference in how they make social media work for them.

“I make a little bit of money here and there from some of my male followers. I’ve sold nude photos and fetish items such as dirty socks and used panties,” Juniper says. “The craziest thing someone asked me for was a vial of my spit. I was all in, but he flaked on the payment.”

Lately Juniper has settled down in New Orleans, Louisiana where she says advertising show schedules is only a small part of what she uses social media for.

“Because my customer base in NOLA is mostly tourists, I find that I don’t usually draw people on that way. It’s a one and done sort of deal down here,” Juniper explains. “Social media has probably helped me the most by allowing me to connect with other strippers. I have been able to share travel tips and trade club info with many girls around the US. Having inside information about the way a club operates before walking in is very valuable in this industry.”

Exotic dancers are part of a diverse, globe spanning professional community. Each has their own story about how and why they started stripping.

“There’s a lot of preconceptions and preconceived notions people have about what a stripper is, the mindset behind it and why we do what we do,” Gia says. “It’s important to understand the diversity … give a person a chance to be a person.”

For some women it’s a gig — something to supplement their income or help pay for their education. For others it’s a craft and a profession that they take very seriously. That makes networking incredibly important. “You want to work somewhere that works for you rather than trying to conform to a mold of something that isn’t you,” Juniper explains.

When Juniper traveled across the country she saw that regional differences can be stark.

“I experienced how different the club scene can be from region to region. California was very competitive and not an easy environment to work in. I was referred to as a ‘bigger girl’ more than once over there,” she observes. “Compared to Texas which was a bit more laid back, I was often complimented on how ‘fit’ I was. People’s attitudes about beauty appear to change based on where they are, so financially I felt some places were better than others to work.”

It’s only recently that a woman like Juniper could so publicly share her adventures as an exotic dancer moving across the country. Many strippers credit the rise of social media as a major influence in making women more comfortable telling their stories and documenting their lives.

“Dancers are definitely changing with the times, they’re definitely keeping up, they’re definitely a lot more confident in the fact that they are dancers,” Gia says. “You know maybe 15, 20 years ago to be so open as a dancer or a sex worker — anything like that — it was just not done. But now you do have the ability to be more confident.”

For many strippers, social media has allowed them to actively fight stigmas around their profession and make themselves more visible.

Brooklyn-based Jacqueline Frances started posting comics based on her club experiences online as part of Instagram’s 100 Day Project while working on her book The Beaver Show. She’s continued building up a following and has her own apparel line called Strippers Forever that sells items like t-shirts that say “off-duty stripper” for dancers to visibly show off their profession with pride on and offline.

“Social media has allowed individuals to be humanized and normalized and I think just acknowledged,” says Stanger, who has been dancing in clubs in Portland for eight years. Stanger is a co-organizer of the Portland Slutwalk and was a key organizer of a 2015 lobbying campaign in Oregon to provide safer working conditions for strippers. Active on social media and open about her life, Stanger also co-hosts the podcast Unzipped PDX with fellow stripper Orchid Souris Rouge.

Society at large has an often contradictory — perhaps hypocritical — relationship with strip clubs and the women who work in them.

In the United States strip clubs are a 7 billion dollar annual industry. They’re often glamorized in music videos and films, even as the dancers themselves are frequently mocked or disparaged. In pop culture strippers often come off as either stupid, sleazy and/or damaged. All the same their dance moves and fashions are frequently sources of inspiration for pop stars and models who work in mainstream entertainment.

In recent years, many women have taken to embracing pole fitness routines, posting photos and videos of themselves doing routines. As the craze caught on many these posts began using the hashtag #notastripper. The hashtag angered many strippers as they wondered what, exactly, was so shameful about being a stripper. In response, Stanger began using the hashtag #yesastripper.

“Pole hobbyists have appropriated our style of movement,” she explains. “At the time there were 5,000 #notastripper posts, today there are 23,000 #yesastripper posts. And I have literally watched this bolster the confidence and community of women in this industry, because it is so much harder to disparage us when our presence is undeniable.”

Stanger recalled when the hashtag #strippershatemebecause began trending on twitter, with several men bragging about doing things like throwing quarters at women, exposing themselves and refusing to tip. It didn’t take long before strippers started joining in on the conversations snarkily telling them (and the rest of the world) why they really hated them.

“They became totally engulfed and swallowed by the people who were originally supposed to be the butt of the joke,” Stanger says. “It’s so much easier for people to joke about killing us, raping us, ripping us off, throwing quarters at us when there’s no clapback. Now there is.”

Strippers have also used social media to fight back against club managers and other contractors that have engaged in exploitive practices. In October 2017, the hashtag #NYCStripperStrike began popping up as strippers in New York City working at hip-hop clubs got fed up with bartenders skimming off their tips — sometimes literally grabbing it off of their stage.

There was also a racial component to the proposed strike: most of the women working the stages at those clubs are black, while most of the bartenders are white or latina. The strippers used social media — as well as engagement with traditional media outlets — to tell their side of the story. Of course, the story was a bit more complicated. What resulted wasn’t a literal walkout strike but a now ongoing effort to raise awareness about workplace conditions — and to change them.

Gia observed those events from afar.

“I worked in New York, and I am very dark, and I had an amazing time while I was there,” she says. She recounts occasional brushes with racism there, but says she never personally experienced anything on the level she was hearing about in social media posts and news reports.

“As far as the strike though, do I think that it’s brilliant that they’re doing something together? Absofuckinglutely,” Gia adds. “ Whenever people can come together and there’s a common thread — even if I didn’t see it, they see something that’s not right — and they came together and said ‘this is not right, let’s proceed,’ that I love.”

Stanger has often used her platform to fight for causes she believes in. In the past she’s promoted her “Thanks Stripping” show where she donates a portion of her tips to organizations like Planned Parenthood and women’s shelters. “Just from advertising on Facebook or Instagram I quadrupled the earnings of the year prior,” she says.

However, stigma still regularly gets in the way even as technology breaks down barriers. In fact, some technology companies have actively erected barriers.

“There is no payment processing system that is widely used that is sex worker friendly,” says Stanger, particularly singling out platforms like Square and PayPal. “They have it in their terms of use that sex work or adult entertainment is forbidden. And so, that’s really interesting. These payment processing companies would make so much more money if they allowed us to do this.”

Strippers have historically performed under stage names for a variety of reasons. One of the chief reasons was to protect women’s privacy and keep their work as strippers confidential. Part of that was about stigma — avoiding family, friends or future employers from finding out and judging them. But it can also be for protection to avoid stalkers and overzealous customers.

Having a social media presence can complicate that. At present Stanger has about 68,000 followers on Instagram. When she goes out to run errands it’s not unusual for her to run into the occasional customer in Portland — and she sometimes gets recognized. “You have to be remember that whatever you post online can be seen by almost anyone in the world,” she says. “And if you build a following that may eventually impact your daily life.”

Stanger said that some women maintain separate sets of social media accounts — one under their real name and one under their performer name. Stanger isn’t particularly self-conscious about it, keeping just one set of accounts. But she does have rules. She makes sure not to post pictures of her car or her home’s exterior online. She rarely shows pictures of her partner or child.

“It’s a really interesting way to be held accountable, but to also understand that you relinquish a lot of your privacy when you start using your social media platform for advertising,” Stanger adds.

In some cases, men have aggressively sought dancers’ private information. In 2013 a man named Robert Hill began making records requests for women working at the club Dreamgirls at Fox’s in Pierce County, Washington. In Pierce County, adult entertainers are required to have a license that includes both their real name and performer name, date of birth, home address, photos and other identifying information.

Hill was making the requests from a jail cell after an arrest for assault in a bar brawl. He has a long history of run-ins with the law, including an earlier arrest for stalking. Hill argued that despite his criminal background he was legally entitled to know what both dancers and club managers looked like and where they lived. These documents are technically public records.

Hill claimed the women should be grateful — he said he was in the social media consulting business and that he would be helping club managers and turning dancers into stars. “They can absorb it, they could ignore, they could act on it. Until they hear it, they’re not able to benefit from me,” Hill told reporters in an interview from his cell. “They could have per-club pages versus just focusing on the dancer.”

Neither the managers nor the dancers had any interest in Hill’s scheme. A group of dancers successfully sued to block the county from giving Hill any more records. But the next year another man, David Van Fleet, started filing requests for information about dancers at the same club.

“I would pray for those dancers by name, I’m a Christian … We have a right to pray for people,” Van Fleet told The News Tribune. The dancers sued again. This time a federal judge ruled in the dancers’ favor arguing that their right to privacy superseded public disclosure laws. But online, hackers and trolls have continued pursuing some women.

“I’ve been fortunate to have avoided any serious problems with stalking. I have had guys online repeatedly bother me from other accounts,” Juniper says. “The funniest thing was this boy who claimed to want to pay me to be his online slave. So I asked him to send me photo verification of his age, but it soon became obvious he was a minor. He has since made three new accounts all with a slightly different version of his username to try and re-follow me, but I just keep blocking him.”

Between the rise of President Donald Trump and the fall of movie mogul Harvey Weinstein, sexual harassment and violence have become central — if deeply uncomfortable — topics of conversation in American life. Some commentators both on the left and right have pointed to the prevalence of pornography and other adult entertainment as drivers of sexual misconduct and of moral decline.

Stanger, who considers herself a committed feminist, balks at that explanation as simplistic and insulting. She adds that as a feminist, she’s particularly frustrated with women who invoke female empowerment in their attacks on adult entertainment and sex work. “They’re not feminists,” Stanger says, “I hate those sorts of women, they’re the bane of my existence.”

Strippers and other sex workers have a name for those activists: SWERFs (Sex Worker Exclusionary Radical Feminists).

“They are policing the movement, the expression, the labor of people who do choose this work. Because are they talking about actual victims of sex trafficking who are not consenting? Or are they talking about people who get up, submit their schedule, drive to work, eat their lunch and head home, because there is a difference,” Stanger explains. “Consent is always the difference.”

Stanger acknowledges that there are abuses in the industry, ones that she and other women have actively fought against. But she insists those on both the left and right of the political spectrum that fixate on porn and sex work are simply using them as scapegoats for much more complex and deeply rooted problems.

“Because if you decide to be a seamstress, you’re a seamstress. If you are living somewhere where you have to work in a sweatshop or you don’t have a choice, someone’s keeping you there, then you’re being fucking trafficked.”

“It’s really frustrating, I almost prefer the right wing nut jobs because at least half of them don’t come into my space,” Stanger adds as she recounts how self-described feminists at times treat her with a mixture of hostility and pity. “I’m fine. The job doesn’t impact me negatively, it’s people who want to hurt me or disparage me for the job I do.”

Gia argues that the notion that “women and women’s bodies as something to be covered up, or that if you’re not covered up there’s no possibility of success,” is itself a sexist and patriarchal notion. She points out that it while dancing at Miami’s King of Diamonds it was often women in the audience that drove her popularity.

Gia used to perform with short hair, what she called her “Grace Jones” look. “Men would be so offended sometimes and say ‘why don’t you have hair?’ And women would look at me and say ‘I want to be like you,’” she recalls. “I’m walking around, I’m dark-skinned, I’m short haired, and I’m completely making the money I want, and I’m happy.”

Juniper has a similar outlook.

“This is my body, my life, my choices,” she says. “I chose a job that I genuinely enjoy.” She says she knows all too well that there is a culture of impunity exploited by people who would look at her as nothing but an object. “Walking around in the streets I am constantly harassed, cat called, sometimes threatened and physically touched by men who feel entitled to my attention,” Juniper says.

Perhaps counterintuitively, at times it’s in the sexually charged environment of the club where Juniper’s body is on full display before gawking men that she feels more comfortable. “There is a very empowering feeling to be in a club and tell a man ‘no,’” she says. “Some people really need to hear that.”

By Kevin Knodell for Medium.

One Comment

увеличение губ филлером

Very nice post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wanted to say that I’ve

truly enjoyed surfing around your blog posts.

After all I will be subscribing to your feed and I hope you write again soon!